This article originally appeared on the Duke Social Science Research Institute website on March 12, 2025.

Dementia currently affects some 6 million people in the U.S. and over 40 million worldwide. As the population ages, it has been projected that dementia cases will double in the next 30 years. With baby boomers reaching over 70 million people in the United States, it seems logical that many people of this generation will be affected by dementia. But what does the data actually show?

In their article, “Changing Story of the Dementia Epidemic,” published in the March 12, 2025 issue of JAMA, Duke University researchers, P.J. Eric Stallard, ASA, MAAA, FCA, Svetlana V. Ukraintseva, PhD, and Murali Doraiswamy, MBBS, FRCP, point out a crucial error in prior estimates.

Findings:

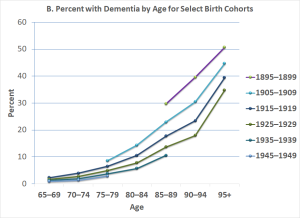

- Prior studies did not adjust for a birth cohort effect – i.e. each successive generation has lower rates than their parents’ generation.

- Risks for dementia may change with successive generations

- Big implications for policy makers and future risk reduction

Why are you interested in dementia-related research?

Stallard: This research continues more than four decades of work on the health and well-being of older persons in the U.S. using data from the National Long Term Care Survey collected by our research team at Duke University. Our research tackles a fundamental question in the biodemography of aging: Were the increases during the past 75 years in life expectancy at age 65 and older accompanied by commensurate declines in the age-specific prevalence rates for severe physical and cognitive impairments? The answer to this question has important implications for the widely anticipated dementia epidemic due to the doubling of the oldest-old population with the aging of the baby boomers in the U.S. My interest in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias started in 1995 when I was asked to use the NLTCS data to generate a model of the clinical progression of Alzheimer’s from the time of diagnosis up to the time of death.

How would you describe this research?

Murali: The goal of our research is to generate accurate risk estimates for dementia and identify what factors may raise or lower the risk. For example, over the last 4 decades, education levels have risen, smoking rates have dropped and treatment of cardiovascular risks and hearing loss has improved all of which may explain why dementia rates dropped. But on the other hand, rising rates of obesity, diabetes and sedentary lifestyle may lead to increased dementia rates in the future.

Some 40% of the risk of dementia may be potentially modifiable so its crucial to understand how attributable risks are changing over successive generations. This will enable people to make changes to lower their risks.

What was one surprising thing you found after looking at the data?

Stallard: Actually, there were two related findings that are best understood jointly:

(1) The overall declines in prevalence rates for dementia observed during 1984–2004 continued during 2004–2024 at almost the same rate—dropping in half every 25 calendar years—with no slowdown at the end of the observation period. I had originally expected the rate of decline to slow down substantially over the past decade.

(2) Each successive birth cohort exhibited systematically lower dementia prevalence rates at each given age than prior birth cohorts. This finding was significant because future age-specific prevalence rates for cohorts are easy to project under the assumption that the observed rates of decline at each age continue into future years. Under this assumption, the impact of the projected doubling of the number of persons at risk to dementia would be substantially reduced. For example, rather than a doubling of the number with dementia over the next 25 years, the increase would be on the order of 10% to 25%.

What should people take away after reading your findings?

Murali: The dementia that is diagnosed at age 70 has its origins in our mid-life. There are about twenty major risk factors for dementia. It’s important for us to know our risks and manage them to lower the chances.

That said, people should not take away from our research that overall dementia rates are going to decline. In fact, overall dementia rates will continue to rise as people live longer, new risks (such as obesity and diabetes) emerge and dementia is detected at earlier stages using more sensitive brain scans or blood tests. That is why finding effective interventions to prevent or delay dementia is an urgent priority for society

What’s next?

Stallard: We need to improve the precision of the estimates in the prior answer and to better understand why the younger birth cohorts exhibited lower dementia prevalence rates than older birth cohorts. This will complement and enhance lifestyle and other interventions aimed at reducing dementia prevalence in younger birth cohorts, given that dementia represents the final stages of long-term neuropathological processes occurring over several decades with multiple opportunities for intervention.